Wastewater and the Septic System

What is a septic tank?

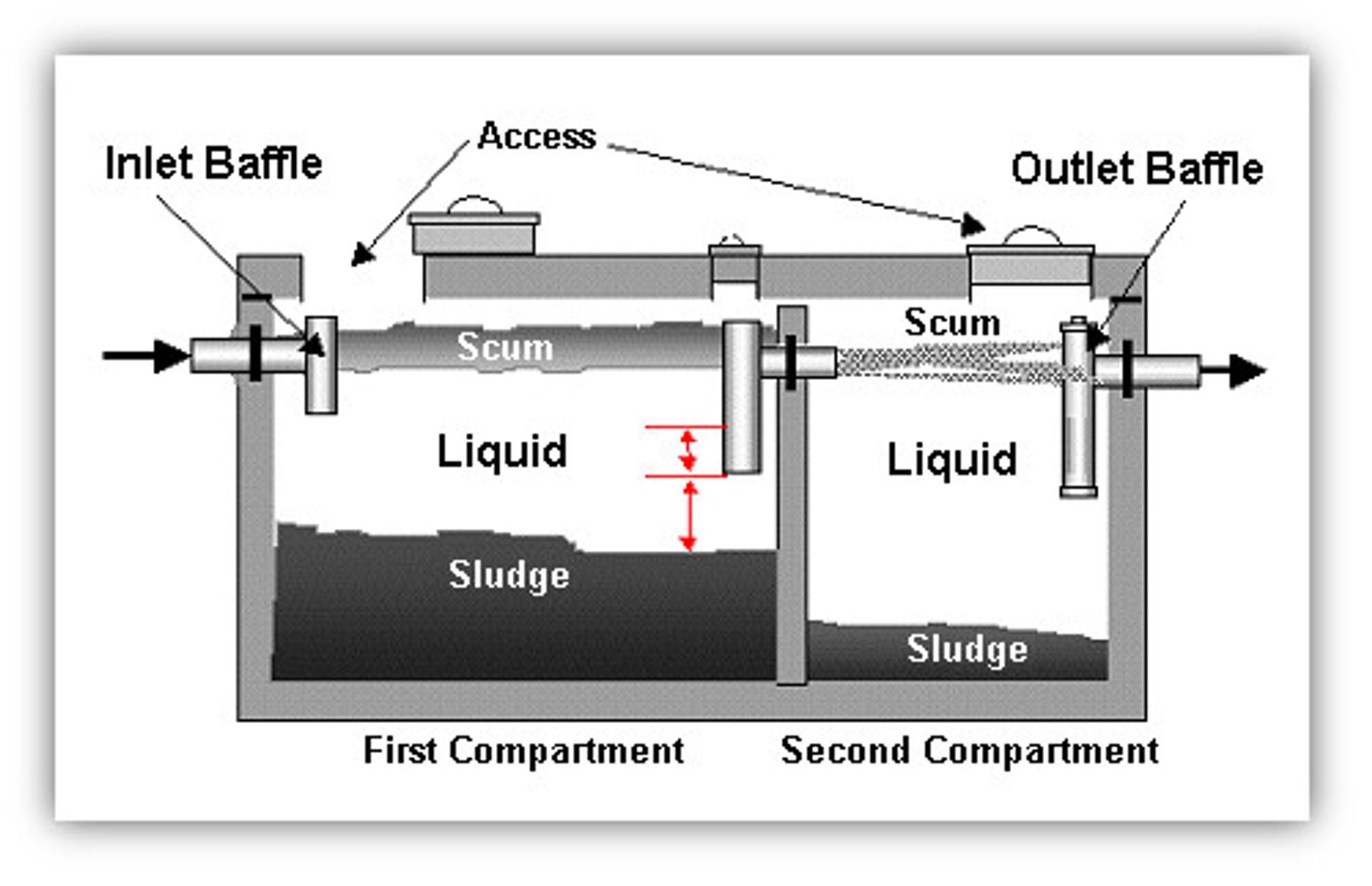

For the 20% of American households and institutions that are not hooked up to a sewer system, everything that goes down any of the drains (toilets, showers, sinks, laundry machines) travels first to the septic tank. The septic tank is a large-volume, watertight tank that provides initial treatment of wastewater by intercepting solids and settleable organic matter before disposal of the wastewater (effluent) to the drainfield.

While relatively simple in construction and operation, the septic tank provides a number of important functions through a complex interaction of physical and biological processes.

What does a septic tank do?

The essential functions of the septic tank are to:

- Receive all wastewater from the house or institution

- Separate solids from the wastewater flow

- Cause reduction and decomposition of accumulated solids

- Provide storage for the separated solids (sludge and scum)

- Pass the clarified wastewater (effluent) out to the drainfield for final treatment and disposal

The septic tank provides a relatively quiescent body of water where the wastewater is retained long enough to let the solids separate by both settling and flotation. This process is often called primary treatment and results in three products: scum, sludge, and effluent.

Scum

Substances lighter than water (oil, grease, fats) float to the top, where they form a scum layer. This scum layer floats on top of the water surface in the tank. Aerobic bacteria work at digesting floating solids.

Sludge

The "sinkable" solids (soil, grit, bones, unconsumed food particles) settle to the bottom of the tank and form a sludge layer. The sludge is denser than water and fluid in nature, so it forms a flat layer along the tank bottom. Underwater anaerobic bacteria consume organic materials in the sludge, giving off gases in the process and then, as they die off, become part of the sludge.

Effluent

Effluent is the clarified wastewater left over after the scum has floated to the top and the sludge has settled to the bottom. It is the clarified liquid between scum and sludge. It flows through the septic tank outlet into the drainfield.

The floating scum layer on top and the sludge layer on the bottom take up a certain amount of the total volume in the tank. The effective volume is the liquid volume in the clear space between the scum and sludge layers. This is where the active solids separation occurs as the wastewater sits in the tank.

How long must liquids remain in the septic tank?

In order for adequate separation of solids to occur, the wastewater needs to sit long enough in the quiescent conditions of the tank. The time the water spends in the tank, on its way from inlet to outlet, is known as the retention time. The retention time is a function of the effective volume and the daily wastewater flow rate:

Retention Time (days) = Effective Volume (gallons)/Flow Rate (gallons per day)

A common design rule is for a tank to provide a minimum retention time of at least 24 hours, during which one-half to two-thirds of the tank volume is taken up by sludge and scum storage. Note that this is a minimum retention time, under conditions with a lot of accumulated solids in the tank. Under ordinary conditions (i.e., with routine maintenance pumping), a tank should be able to provide two to three days of retention time.

As sludge and scum accumulate and take up more volume in the tank, the effective volume is gradually reduced, which results in a reduced retention time. If this process continues unchecked—if the accumulated solids are not cleaned out (pumped) often enough—wastewater will not spend enough time in the tank for adequate separation of solids, and solids may flow out of the tank with the effluent into the drainfield. This can result in clogged pipes and gravel in the drainfield, one of the most common causes of septic system failure, and also in pathogenic bacteria and dissolved organic pollution.

In order to avoid frequent removal of accumulated solids, the septic tank is (hopefully) designed with ample volume so that sludge and scum can be stored in the tank for an extended period of time. A general design rule is that one-half to two-thirds of the tank volume is reserved for sludge and scum accumulation. A properly designed and used septic system should have the capacity to store solids for about five years or more. However, the rate of solids accumulation varies greatly from one case to another, and actual storage time can only be determined by routine septic tank inspections.

How do bacteria fit in?

While fresh solids are continually added to the scum and sludge layers, anaerobic bacteria (bacteria that live without oxygen) consume the organic material in the solids. The by-products of this decomposition are soluble compounds, which are carried away in the liquid effluent, and various gases, which are vented out of the tank via the inlet pipe that ties into the building plumbing air vent system.

Anaerobic decomposition results in a slow reduction of the volume of accumulated solids in the septic tank. This occurs primarily in the sludge layer but also, to a lesser degree, in the scum layer. The volume of the sludge layer is also reduced by compaction of the older, underlying sludge. While a certain amount of volume reduction occurs over time, sludge and scum layers gradually build up in the tank and eventually must be pumped out.

EnviroZyme’s Concentrated Grease Control 10X and Septic Treatment products can be used if the effective volume and/or retention time of a septic tank is not great enough to prevent non-clarified wastewater from flowing through the outlet.

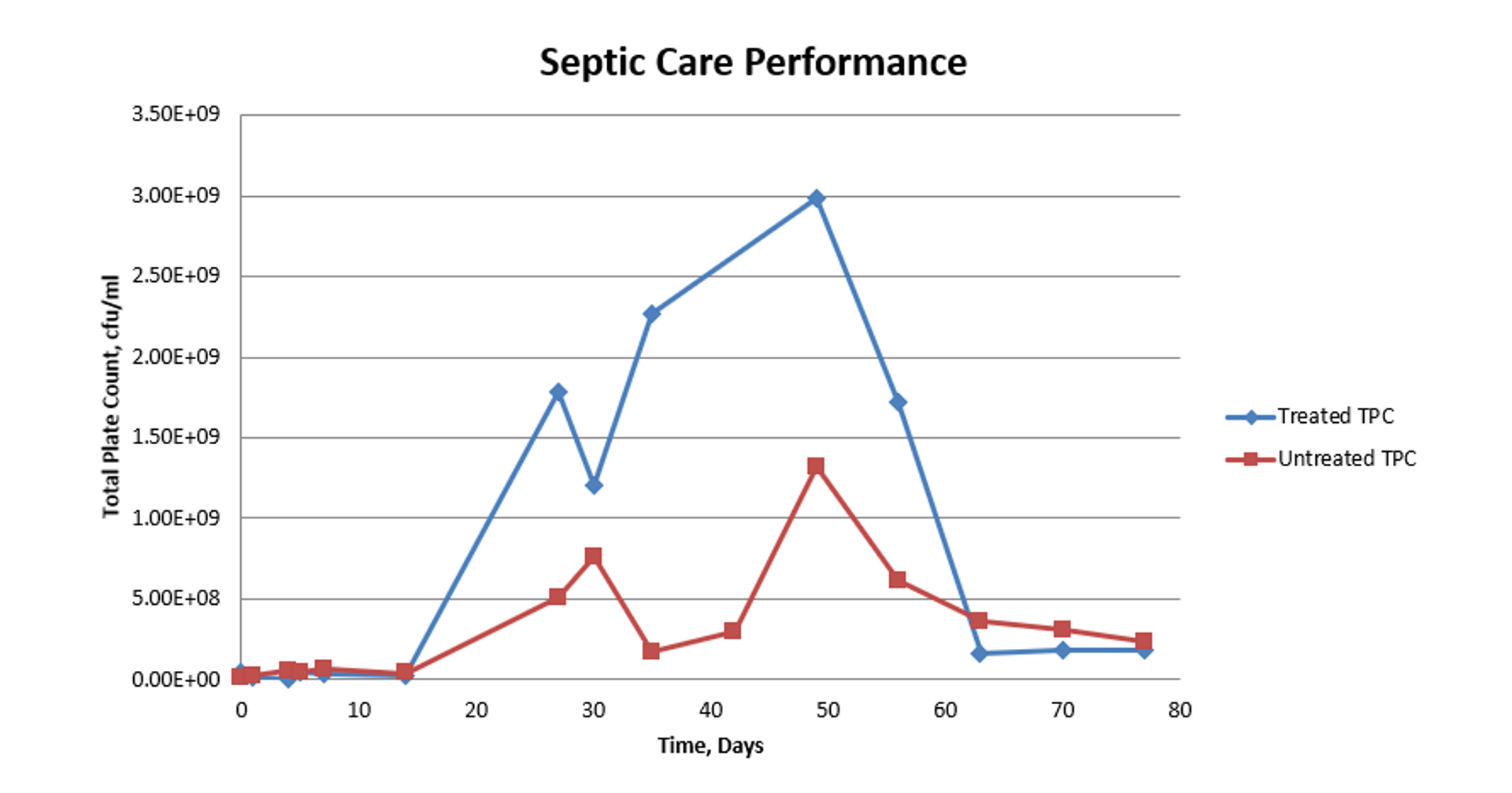

The bacteria in these products will raise the total plate count, and consumption of the organic compounds in the sludge and scum layers will accelerate as a result. This effectively reduces those layers and the frequency with which a septic tank needs to be pumped out.

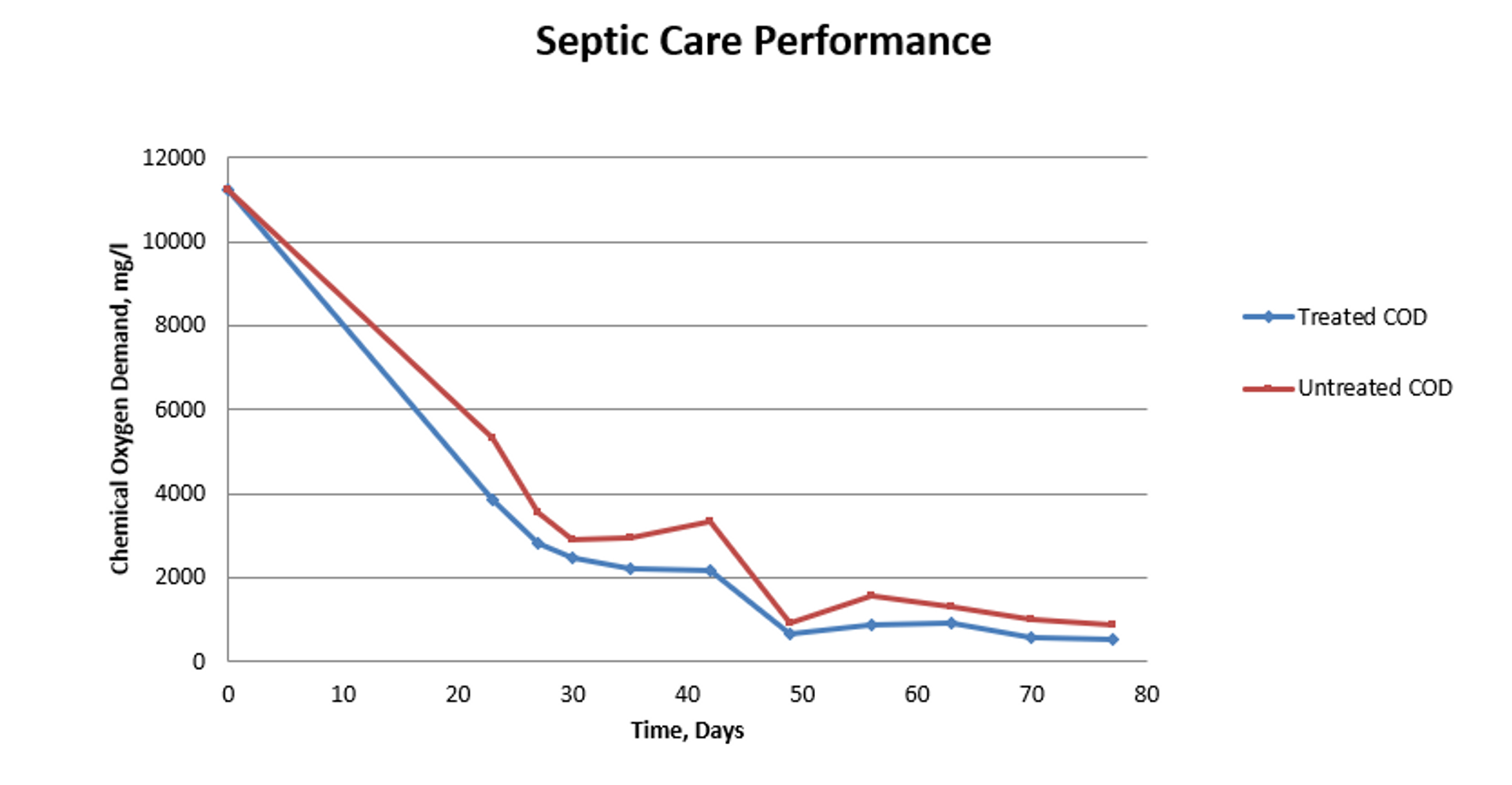

In an experiment, we set up two aquariums with fresh food that approximated the sugar/starch/protein/oil ratios found in the US diet and treated one but not the other with Septic Treatment.

As expected, we documented a higher total plate count in the treated tank, noting that after about 45 days, the total plate counts in both sides returned to the same level. This was because natural wastewater has bacteria in it already, and they eventually resumed dominance in the biomass. This time line indicates a monthly treatment program for best results.

We also measured the carbonaceous biochemical oxygen demand (cBOD) in the clear liquid portion of each tank, about 10 inches below the surface. Both tanks showed a decrease over time because we were not adding ‘new’ food after the initial charge, but the treated tank showed a 36% reduction in cBOD compared to the control. This means that, once treated, a septic tank’s effluent will also reduce the amount of dissolved organic pollution entering the environment.

Interested in finding out more about how our bacteria can help?